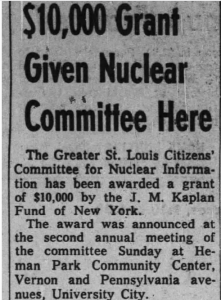

When the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information touted its $10,000 grant from the J.M. Kaplan Fund, the public didn’t know the foundation was a CIA front.

first published at firstsecretcity.com

The announcement came at the second-annual meeting of the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Safety at the Heman Park Community Center in University City, Mo. on May 8, 1960. More than 500 attendees heard the good news. Their organization had received a $10,000 grant from the J.M. Kaplan Fund to pursue its laudable work. It was cause for celebration. But they were unaware of one string attached to the generous gift, a nettlesome detail that may have dampened their enthusiasm that long ago spring evening: the Kaplan Fund was a CIA front.

Then as now there were ramped up concerns over an ongoing public health crisis. In 1960, the problem was the wind-driven dispersal of nuclear fallout. St. Louisans were worried about the proliferation of nuclear weapons during the Cold War, and the potential health effects that atmospheric testing was having on their children. To address the issue, they enlisted leaders of the scientific community to study the effects of radiation. There was no reason for them to suspect that their local organization’s goals had been subverted. That possibility wasn’t on anybody’s radar back then.

It’s a question that’s remained unasked until now; a footnote to history that’s been buried in the First Secret City for 60 years.

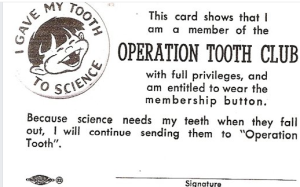

The citizens’ committee, a coalition of parents, educators, medical professionals and scientists, had formed in 1959 to measure Strontium-90 levels by collecting the baby teeth of elementary school children in the St. Louis area and elsewhere. The radioactive isotope, known to be present in nuclear fallout, concentrated in human bones and teeth, particularly growing children who consumed milk. Kids were encouraged by parents, teachers and dentists to give their teeth to science instead of the tooth fairy. In return, they were rewarded with a membership card and button to the Operation Tooth Club. The program was called The Baby Tooth Survey. The director of the survey was Dr. Louise Reiss, and its scientific advisory board included Washington University biologist Barry Commoner.

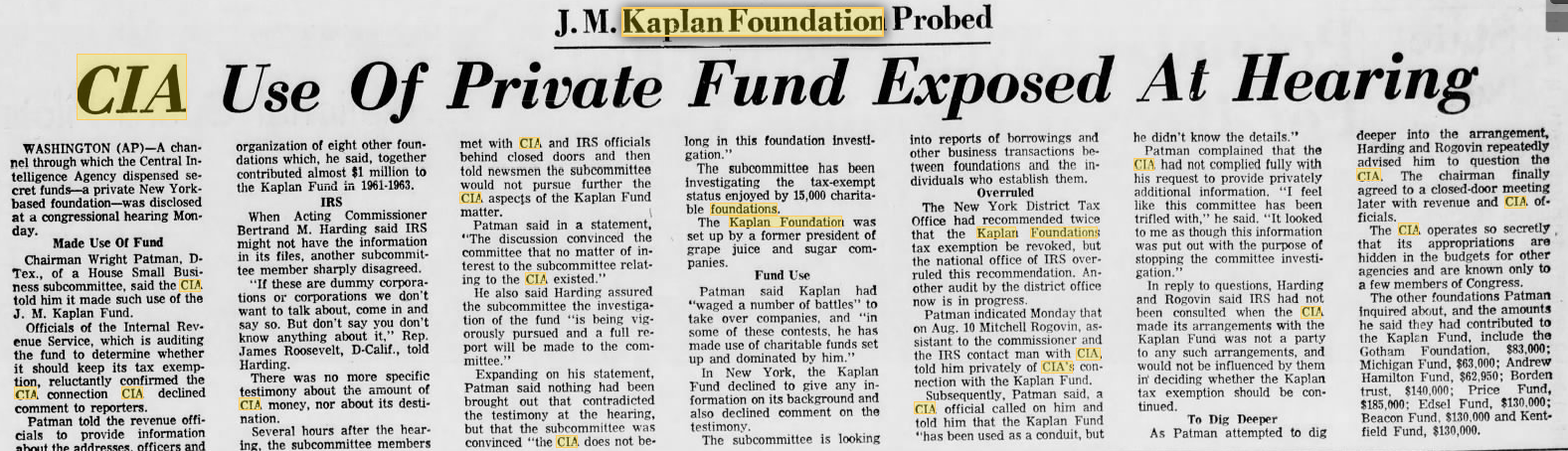

The keynote speaker at the 1960 meeting of the committee was internationally renowned anthropologist Margaret Mead, according to accounts published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and St. Louis Globe-Democrat. The same news accounts also reported the generous contribution from the J.M. Kaplan Fund of New York, which later would be revealed in congressional hearings to be a covert conduit for funneling CIA cash.

U.S. Rep. Wright Patman, a Texas Democrat, outed the private foundation’s ties to the CIA at a hearing of his House Small Business Sub-committee on Aug. 31, 1964. In addition to the congressional probe, the Kaplan Fund was also under investigation by the Internal Revenue Service, which confirmed the foundation’s ties to the CIA, according to a news story in the New York Times. Jacob M. Kaplan, former head of Welch’s Grape Juice company and founder of the non-profit charity, had already garnered IRS attention for using the fund as a tax dodge. Patman’s hearings determined that the Kaplan Fund had been used as a CIA front from 1959 to 1964.

It is uncertain whether the money donated to the St. Louis group was part of the CIA’s clandestine operations, but the agency’s extensive use of private foundations, including the Kaplan Fund, gained further exposure in subsequent investigative reports that appeared in the late 1960s in the Texas Observer, Nation, and Ramparts magazines.

Mead’s presence at the St. Louis meeting, where the the Kaplan Fund’s generosity was announced, is intriguing because of her previous involvement in espionage dating back to World War II, when she and then-husband Gregory Bateson, also an anthropologist, produced propaganda in the South Pacific for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the CIA.

In the early 1950s, Bateson tripped on LSD furnished to him by Dr. Harold Abramson, who was part of the agency’s top-secret MK-Ultra project, a program that experimented on the use of hallucinogenic drugs and other means to influence and control human behavior. After scoring more of the CIA’s acid, he turned on his friend Alan Ginsberg, the beat poet. Funding for Abramson’s LSD research was funneled through two other CIA cutouts: the Geschickter Fund for Medical Research and the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation.

In late November 1953, Abramson — an allergist — acted as the unlicensed psychiatrist of Frank Olson, shortly before the Army biological warfare scientist fell to his death from a 13th floor window of the Statler Hotel in New York City. Olson had received counseling from Abramson for anxiety and depression after being wired up on acid by the CIA. While under the influence of the drug, Olson voiced ethical concerns about his germ warfare research to colleagues, which was considered a national security breach by the agency. Abramson and Olson had previously worked on classified aerosol research at Camp Detrick, the Army’s chemical warfare research facility in Frederick, Maryland. Olson’s unsolved death is the subject of the 2017 Netflix series Wormwood by Errol Morris.

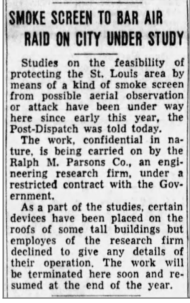

Coincidentally, 1953 is also when the Army began its secret aerosol testing in St. Louis. Parsons Corporation ran that covert military operation out of an office in the 5500 block of Pershing Ave. in St. Louis. The tests involved the spraying of poor, inner-city neighborhoods without residents knowledge. Workers who participated in the study were also kept in the dark. When the testing became known about decades later, the Army said it used zinc cadmium sulfate, which it claimed wasn’t harmful to human health. In the 1990s, former Parsons employees said they believed their cancers were caused by being exposed to the chemicals used in the tests. The EPA announced last year that Parsons Corporation was awarded the main contract for the clean-up of radioactive contamination at the West Lake Landfill site in St. Louis County. The contamination is from uranium processing conducted by Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in St. Louis for the Manhattan Project.

The Baby Tooth survey, which began six years after the aerosol testing, found a correlation between atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons and Stontium-90 levels in children’s teeth in the St. Louis area. But its scientific findings were in some ways eclipsed by the survey’s public relations successes. Publicity garnered by the Baby Tooth Survey is credited with spurring the passage of the 1963 Nuclear Test Ban Treaty between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

An earlier covert collaboration by the Atomic Energy Commission, Air Force and Rand Corporation to measure Strontium-90 in humans received harsh criticism, after it was revealed that researchers obtained scientific data by snatching bodies. Beginning in 1953, Project Sunshine collected bone sample from cadavers, including those of stillborn babies.

Gathering scientific data by collecting the baby teeth of living children was deemed more acceptable and received unquestioning public cooperation.