J.J. Maloney traded a knife for a pen, swapping a life of crime for a career in journalism.

copyright 2021 by C.D. Stelzer

An earlier version of this story appeared in the St. Louis Journalism review in 2008 and Focus/midwest magazine in 2010.

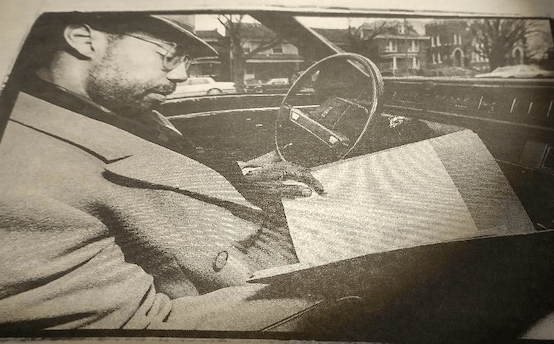

He chain-smoked. The brand varied with the decade: L&Ms or, later, Marlboro Lights. In prison he preferred Camels, when he could afford them. Otherwise, he rolled his own from pouches of Ozark-brand tobacco, manufactured and distributed for free at the Missouri Penitentiary. It’s the smoking that eventually killed him. By then, most of his running buddies from the joint were long dead, victims, for the most part, of their own malevolent ways.

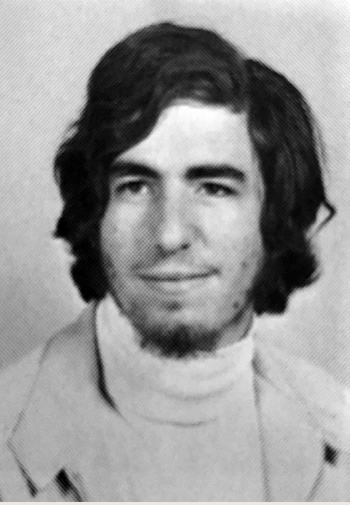

That J.J. Maloney survived is remarkable. But his rise from convicted murderer to award-winning investigative reporter for the Kansas City Star is a feat unparalleled in the annals of American journalism. Maloney joined the newspaper’s staff after being paroled in 1972. At the time of his release, he had served 13 years of a life sentence for killing a South St. Louis confectionery owner during an attempted robbery. Maloney was 19 years old when he committed the crime.

Kevin Horrigan, a cub reporter at the Star in 1973, remembers Maloney as an affable colleague but one who stood apart. “There was just something there, and it didn’t fit in with everybody else,” says Horrigan, now an editorial writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “It was like he was from another planet. He was one of those guys who was constantly fidgeting, or his knee was pounding up and down. Given where he’d come from, it’s easy to figure out why.”

Maloney’s prison record listed him as 5-foot-9 and 145 pounds. He was not from another planet, but he was from another time. When he entered prison, Dwight Eisenhower was president; when he came out, the Watergate burglary had been committed.

Maloney owed his freedom to Thorpe Menn, the Star’s literary editor, who had supported his parole and helped him get his job at the newspaper. Maloney had garnered the editor’s attention in 1961 through a poem he had submitted to the Star, which then printed verse on its editorial page each day. Maloney’s formal education had ended in the ninth grade, but Menn recognized raw talent when he saw it. He rejected Maloney’s poem but continued to correspond, providing him with professional advice and personal guidance. Maloney thought of Menn as the father he never had.

The only thing his real father ever gave him was his name. Joseph John Maloney Sr., a shoemaker by trade, walked out of his son’s life in 1943, when he was 3 years old. A year after his parents divorced, a hit-and-run driver killed his brother, Bobby. After his mother suffered a nervous breakdown, the court remanded him to the custody of the St. Joseph’s Catholic home for boys in St. Louis, where he stayed for nearly a year.

By the time Maloney returned home, his mother had remarried. His stepfather, Julius “Dutch” Gruender, an ex-con, became Maloney’s less-than-sterling guardian. Gruender, a housepainter, had a string of arrests and convictions for car theft and burglary dating back to 1926. At the time of his marriage to Maloney’s mother, he had only been out of the Missouri Penitentiary for a year.

While in prison, Gruender met and befriended Elmer “Dutch” Dowling and Isidore Londe, lieutenants of East St. Louis mob boss Frank “Buster” Wortman. Gruender’s association with these gangsters continued long after his parole. The housepainter soon introduced his young stepson to the underworld, taking Maloney with him on occasional visits to the Paddock Lounge, Wortman’s bar in East St. Louis, which was a hangout for organized crime figures. Maloney also tagged along when his stepfather drove to Jefferson City to visit a friend still incarcerated at the penitentiary. Though he avoided further trouble with the law, Gruender acted as a courier for Wortman.

In 1952 the family moved to a farm in New Florence, Mo., a small town 65 miles west of St. Louis. Gruender used carpentry skills acquired in prison to rehab the old farmhouse, and he showered Maloney with gifts, including a motorcycle and a shotgun. Beneath the outward generosity, however, Gruender was an angry and hardened man who drank heavily and sometimes abused his wife and stepson.

The Road to Perdition

On Dec. 19, 1945, at the age of 14, Maloney ran away from home for the first time.

“I was prepared,” Maloney recalled later. “ I had another change of clothes, a pound of fudge, a loaf of bread, 14 silver dollars, and my old man’s .38 was buried in the bottom of the sack.” Despite his preparations, Maloney was quickly apprehended after stealing a car and spent the night in the Montgomery County Jail. The judge put him on probation.

The next year, Maloney ran away again. This time he made it as far as Hannibal before crashing a stolen car. The second incident earned him his first stint in the reformatory at Boonville.

After his fourth escape from Boonville, juvenile authorities transferred him to Algoa, the state’s intermediate reformatory, where his behavior worsened. Over the next year and a half, Maloney was put in solitary confinement dozens of times for attempting to escape, instigating a riot and other infractions. During a short parole in 1957, Maloney was arrested in Kansas City on suspicion of burglary and carrying a concealed weapon.

Despite his abominable record, the state had little choice but to parole him in January 1959, a few months after he turned 18. Maloney then married a former inmate of the girls’ reformatory at Chillicothe, and they moved to Alabama—but the marriage fell apart. After his return to Missouri, his parole officer committed Maloney to State Hospital No. 1 in Fulton for psychiatric observation. While confined at the hospital, Maloney met and fell in love with a fellow patient, 16-year-old Edith Rhodes, who had been transferred from Chillicothe.

“Only in an institution can love hit that hard and that fast,” Maloney wrote. “Edith was a strangely magnetic girl. … She seemed fragile and shy, yet she wasn’t. She was 16 and insisted she would commit suicide before she was 21, because she had a fear of not being beautiful. …”

After six weeks of observation at Fulton, Maloney was allowed by the parole board to enlist in the Army. He was assigned to the Army Signal Corps School at Fort Gordon, Ga. His military career lasted just three months: He went AWOL on Nov. 3, 1959.

While absent without leave, Maloney worked briefly for a carnival in Florida before returning to Missouri. On the evening of Dec. 11, he picked up Rhodes in Columbia at an apartment she was sharing with another girl. The two returned to St. Louis early the next morning on a Greyhound bus. They registered at the St. Francis Hotel, at Sixth and Chestnut, under the name Mr. and Mrs. John Ducharme of Jacksonville, Fla. That evening Maloney, armed with a hunting knife, robbed the clerk at another downtown hotel.

The couple then took a cab to the Soulard neighborhood in South St. Louis. Shortly before 8 p.m., Maloney dropped Rhodes off at the apartment of an acquaintance, then walked to a nearby confectionery, located at 1100 Lami Ave. Entering the store, he pulled a hunting knife and demanded money from Joseph F. Thiemann, the 74-year-old store owner.

“When he made the demand for money, he and Thiemann began struggling,” according to the confession Maloney later gave St. Louis police. After Maloney punched Thiemann in the face several times, the old man agreed to hand over the cash. “Thiemann then reached into his back pocket as if to get the money and came out with a revolver and fired one shot, which apparently went over his [Maloney’s] head.” Maloney reacted by stabbing the storeowner in the stomach. In the ensuing fight, the pistol fired a second time, striking Thiemann in the leg. Maloney then wrested the gun from his victim and fled. Thiemann died as a result of the wounds he sustained in the fracas.

Less than two months later, Maloney pleaded guilty to murder and armed robbery, and Circuit Judge James F. Nangle sentenced him to four concurrent life sentences. He would serve the next 13 years at the Missouri Penitentiary, in Jefferson City—arguably the worst prison in the United States at the time.

Inside the Walls

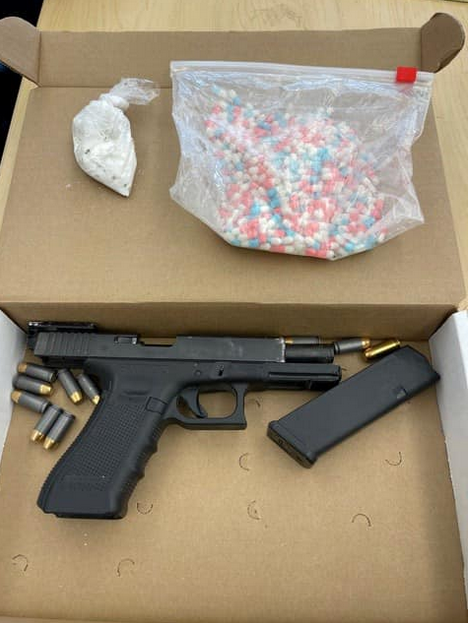

“When I went to the Missouri Penitentiary at Jefferson City, in February 1960, there were 2,500 men inside ‘the walls,’” Maloney later told readers of the Kansas City Star. “The white convicts slept three to a cell (except for several hundred in one-man cells). The blacks slept as many as eight to a cell. “Stabbings and killings, robberies and rapes were common. Dope was easier to get in prison than it was on the streets. There were men in prison who were said to make more money each year from dope and gambling than the warden was paid. There were captains on the guard force who owed their souls to certain convicts.

“You never knew whom you might have trouble with. The reasons for murder and mayhem made little sense to anyone except the convicts. So hundreds of men carried a knife or had one they could get to one in an emergency.

“If you are young and good looking, you can count on being confronted again and again. If you have money, there will be people who want it. If you are helpless, there are people who will try to make a reputation at your expense. Or you may simply say the wrong thing to the wrong person.

“You never know for sure what is going to happen from day to day in prison. …”

A prison psychiatrist who evaluated Maloney shortly after his arrival characterized him as a “socially diffident individual … who seems to take a half-humorous rejection of the whole affair.” If Maloney’s initial demeanor seemed inappropriately aloof given the circumstances, it didn’t take long for his mood to turn into a malevolent rage.

On Aug. 26, 1961, Maloney’s girlfriend, Edith Rhodes, was murdered near Huzzah Creek in rural Crawford County, Mo. She had eloped from the state mental hospital in Fulton and gone on another crime spree, this time with a 22-year-old hoodlum from Flat River. David Moyer, who confessed to the slaying, first told authorities that the girl shot herself and he had fired a second shot to end her pain. A sheriff’s posse pursuing the fugitives heard the shots and found Moyer lying next to the body.

On hearing the bad news, Maloney vowed to kill Moyer and tried to escape. His prison record over the next few years is a litany of major conduct violation:. In addition to the failed escape attempt, the prison administration cited Maloney for stabbing another inmate, manufacturing zip guns, using stimulants and committing sodomy. As a result, he was put in solitary four times and sentenced to the “hole” another 18 or 20 times. Solitary confinement involved long-term segregation, whereas the hole was a short-term punishment, usually a 10-day stint, during which prisoners were deprived of cigarettes, bedding and sometimes clothing.

Freed by Verse

Maloney had reached his nadir. By any measure, he had to be considered beyond salvation, a lost cause. But his mother remained faithful: She never gave up. She corresponded. She visited. She sent money, clothing, food, stamps and other items. She also acted as Maloney’s liaison with the outside world.

Through her encouragement, elderly attorney Mable Hinkley began to correspond with Maloney. Hinkley, a former St. Louis Globe-Democrat Woman of the Year, was an early advocate of prison reform and used her social standing to influence decisions of the Missouri Department of Corrections. Maloney had been in solitary confinement for nearly four months after his escape attempt when Hinkley contacted him.

In her first letter, Hinkley advised Maloney to seek divine guidance, but she also offered him a more down-to-earth deal. “Your mother tells me that if you give your promise to do something, you keep your word,” Hinkley wrote. “Will you make a promise (and keep it) not to try and run away—to obey the rules of the prison and try to do whatever work is assigned to you? If you will make these promises, I will ask the warden to take you out of solitary confinement.”

She kept her end of the bargain. In June 1964, at Hinkley’s urging, Warden E.V. Nash released Maloney from solitary and assigned him to the newly formed prison art class.

Exposure to art ignited Maloney’s innate creative streak. Sam Reese, an older convict who had gained national recognition for his oil paintings and cartoons, served as his role model. Maloney’s own artwork took awards at state and county fairs and was exhibited at a gallery in Paris.

But Maloney became more devoted to writing as he matured.

“Joe, which is what his friends called him, and I shared a cell in C-Hall during 1965-66,” recalls former inmate Frank Driscoll. “We worked on the fifth floor of the prison hospital, which is to say the psych ward. … By the time we were cellies, Joe had straightened up his act and was staying out of trouble, working on his parole. That, of course, was back in the day, when a lifer could still aspire to being released on parole. He was always writing something—stories, critiques, opinion pieces and, yes, poetry.”

Maloney had no way of knowing the significance that his verse would ultimately play in redirecting his life.

“I did what all young poets do, I tried to write a nice little rhyming solution to all the problems of the universe,” he later wrote. “Having written it, my next problem was deciding where to send it. In those days the Kansas City Star printed a poem on the editorial page every day, so I mailed the poem to the Star. A few days later I received a letter from Thorpe Menn, literary editor of the Star, who rejected the poem but said he liked the last four lines. He encouraged me to keep working on the poem, and asked me to stay in touch with him. I was impressed that the literary editor of a famous newspaper would write to me. I was even more impressed that he did not ask why I was in prison, or for how long. He wrote to me as if I were just another person, another young writer.”

It was the beginning of a long-term relationship carried out by correspondence. Menn became his mentor, giving guidance and critiquing his poetry and prose. Maloney worked on his writing for as much as six hours every evening. Menn patiently waited until 1967 before publishing one of Maloney’s poems in the Star. By then, the prison-bound poet and writer had been published in numerous other venues, including Focus/Midwest, a St. Louis–based magazine founded by Charles Klotzer, publisher of the Saint Louis Journalism Review.

Maloney expanded his connections in the literary world, writing to such luminaries as R. Buckminster Fuller, John D. MacDonald, William Buckley and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. At Menn’s suggestion, he started writing book reviews for the Star. He also worked diligently to establish a national writers’ association for prisoners. Meanwhile, Menn had interested Random House in publishing a book of Maloney’s poetry. In late 1967, the parole board indicated the possibility of Maloney’s being released early the next year.

But as quickly as his cell door seemed to have started to creak open, the steel bars slammed shut again. Warden Nash committed suicide. His replacement, Harold R. Swenson, imposed extreme restrictions on all communications with editors and publishers to stop a book from being published by another prisoner, a notorious escapee.

As a result, Maloney’s letters to Menn started coming back undelivered. Moreover, correspondence regarding his book of poetry had to be routed through his mother. The delays in communications eventually killed his deal with Random House. Books sent to him for review were screened by the prison administration and sometimes rejected.

Instead of zip guns or knives, Maloney fought back with the law as his weapon.

He filed suit against the Department of Corrections, arguing that his constitutional rights under the First Amendment had been violated. His defiance dashed his hopes of gaining parole and put him at odds with the prison administration for the remainder of his sentence.

Five more years would elapse before Maloney finally made parole, during which time Menn continued to support and encourage his writing. The literary editor was with Maloney’s mother on Sept. 25, 1972, when Maloney walked out of prison for the last time. They drove to Kansas City together and toured the Star’s editorial offices. The next day, Maloney returned to the newsroom not as a guest but as an employee.

Natural-Born Reporter

In advance of his release, Tom Eblen, then the Star’s city editor, had written a letter to Maloney, offering him a three-month contract at a monthly salary of $550. Despite the low wages, the offer was priceless because it cinched his parole. Star reporter Harry Jones Jr. had hatched the idea of hiring him as a temporary “consultant” for an in-depth series of stories on prison systems in Missouri and Kansas. Menn then sold the proposal to Cruise Palmer, the executive editor.

Maloney’s good fortune was twofold: He had belatedly benefited from the prison-reform movement of the 1960s and also from the unique ownership structure of the Kansas City Star, then employee-owned. On his death, in 1915, the founder of the paper, William Rockhill Nelson, had willed the Star to his employees. That arrangement was still in place in 1972. This meant that senior editorial staffers such as Menn, who had accumulated large stock holdings in the company, could negotiate with management on a more even level.

Jones and Maloney collaborated for months on the prison project, sharing the reporting and writing duties. Their stories ran as a four-part series in April 1973.

“We visited every institution of correction for adults and juveniles in both Missouri and Kansas, plus Leavenworth and Marion in Illinois, which at the time was the Alcatraz of the [federal] system,” says Jones. … “He proved to be an invaluable ally. When we would go in together to interview somebody, a prisoner or the warden or the guards, we’d start off and they would be talking one way and the minute they found out about Joe—and what his background was—it was like administering truth serum. All of a sudden their stories would change. It was uncanny.”

In the first installment of the series, Maloney gave a lengthy first-person account of life inside the Walls in Jefferson City. Before his contract expired, the Star hired him as a full-time general-assignment reporter. The prison series later won the Silver Gavel Award from the American Bar Association.

Maloney excelled as a feature writer but eventually became better known as an investigative journalist covering a wide range of issues, including labor racketeering, white-collar crime, drug trafficking and mental health.

In 1975, Maloney and Jones teamed up again to cover the corruption and violence surrounding a power struggle among factions of the Kansas City Mafia. Competing mob interests were in the midst of fighting for control of the River Quay entertainment district.

The two reporters began knocking on doors, talking to area business owners. They also interviewed city and federal law-enforcement authorities and pumped confidential sources for information. By checking liquor-license applications, Maloney determined that mobsters or their relatives secretly owned several restaurants and bars in the River Quay.

Maloney frequented the mob hangouts at night to develop leads. On one occasion Jones accompanied him to the Three Little Pigs, an after-hours café that was a favorite of the Mafia. “All the hoods would congregate there, drinking coffee,” recalls Jones. “We just went in there one night to sit and watch. Talk about stares. I was glad to get out of there.” Before they departed, Jones overheard the bodyguard to Carl “Corky” Civella threaten to rape Maloney. If the remark bothered Maloney, he didn’t show it.

“He was kind of fearless,” says Jones. “I was impressed. He was a gutsy little guy. He had seen his share of bloodshed. It was curious, too, how they seemed to hate Joe more than me, although our names appeared together on stories. But the mob kind of looked at Joe as a turncoat. Having been a convict, they thought he should have respected their trade a little more than he did.”

In a sense, Maloney did respect their trade. He had learned about it from his mobbed-up stepfather. Maloney added to his underworld knowledge in prison, where he befriended fellow inmate John Paul Spica, a St. Louis Mafia soldier. More important, Maloney understood that the roots of the problem ran deep in the Kansas City political establishment and business community and that there was a kind of mass denial regarding corruption.

“In the mid-’70s, some Star editors were even reluctant to print the word ‘Mafia,’” Maloney later wrote. Maloney was also keenly aware that local law-enforcement officials were hesitant to use the M-word.

“This was the town of Tom Pendergast, one of the most powerful Mafia/machine bosses in U.S. history,” Maloney wrote. “Pendergast was long gone, but his machine was anchored in place. The mob continued to influence the police department, city hall, the county courthouse and the state legislature. … The Kansas City Mafia wielded considerable economic clout—controlling several banks [and] owning ten percent or more of the taverns and nightclubs in the city. …” Its far-flung empire stretched all the way to Las Vegas, where the KC mob oversaw the skimming of millions of dollars from casinos.

But back in Kansas City, a rift had developed among three branches of the local mob: the Cammisano, Spero and Bonadonna clans. Maloney sensed that the feud was about to erupt into open warfare.

At the same time, dissension was brewing in the newsroom. Maloney argued that the Star should immediately expose the Mafia’s infiltration of the River Quay. His editors opposed the idea. They preferred a more cautious approach, advising that the coverage be focused more indirectly on corruption inside the city’s liquor-control agency. Jones agreed with them.

“I remember telling him, ‘Joe, let’s just wait until they start killing each other,’” says Jones. “It didn’t take very long for that to happen. People started dying. People [were] shot and blown up.”

In July 1976, David Bonadonna, the father of Fred Bonadonna, owner of Poor Freddie’s restaurant in the River Quay, became the first victim. He was found shot to death and stuffed into the trunk of his car. Three River Quay nightclubs were soon torched or bombed, and the list of gangland hits rapidly grew. Over the next two years, eight more mob-related murders would go down before the violence subsided.

Because of their advance legwork, Maloney, Jones and staff reporters Bill Norton and Joe Henderson uncovered developments in the midst of the mayhem sometimes before federal and local law-enforcement authorities.

At one point Joe Cammisano called Maloney and said: “Mr. Maloney, I realize you have a job to do—but do you have to be so intense?”

After the Star ran a story implicating Cammisano’s brother William “Willie the Rat” Cammisano in the Bonadonna slaying, members of the two families demanded to rebut the allegation, which was based on an FBI affidavit. At a tape-recorded meeting held in the Star’s conference room, Fred Bonadonna refuted any possibility that Willie Cammisano had had anything to do with the death of his father. The Star published a verbatim transcript of his claims in its next edition.

“The next day I called Bonadonna,” Maloney recalled later. “I asked him if he’d read the story, and if it had helped him any. He said, ‘You’ve saved my life, for the time being, anyway.’”

Bonadonna was one of Maloney’s confidential sources. He had publicly refuted the Star’s story simply to keep from being killed. In subsequent tape-recorded telephone interviews with Maloney, Bonadonna said that the Mafia had also targeted him for execution. Bonadonna disappeared in 1978, presumably into the federal witness-protection program. The same year, Maloney’s byline disappeared from the pages of the Star when he quit the paper in a dispute over overtime pay. By then the Star had been bought by Capital Cities, a media chain with a history of poor labor relations. In the wake of the mob violence, the River Quay was all but abandoned, with only six liquor licenses remaining in the district, down from 28 a few years earlier.

Maloney ended up moving to the West Coast. He reported for the Orange County Register in 1980 and 1981. While at the Register, he covered a series of murders attributed to the “Freeway Killer,” a name of his invention. He also published two autobiographical crime novels. The first, I Speak for the Dead, is a fictionalized account of Kansas City’s mob war, drawn straight form his clip file. His second novel, The Chain, is based on his years behind bars, including his incarceration at the Missouri Penitentiary and the old St. Louis City Jail.

Maloney moved back to Kansas City, perhaps drawn by memories of his glory days. In later years he worked as a freelance writer and as an editor for the alternative press. He pitched various book proposals and collaborated on at least three different screenplay adaptations of his first novel, but none of the projects came to fruition. In the late 1990s, shortly before his death, he established a Web site, crimemagazine.com, which is maintained by his friend J. Patrick O’Connor, former owner of the New Times, a now-defunct alternative weekly in Kansas City.

“He had his demons,” says Mike Fancher, an editor who worked closely with Maloney, “but I know that for the time that he worked for the Star he did some absolutely amazing work that I don’t think any other journalist could have possibly done.”

C.D. Stelzer, a St. Louis-based freelance writer, is working on a biography of the late J.J. Maloney.